We are too little to lose each other

From Karen Coats's Looking Glasses and Neverlands:

"Recipes for stories are passed across cultures and generations. In industrialized countries, they can become standardized and bland in their mass production or even fortified with things we have been told are good for us.... From our first beginnings, we are fed stories, embraced by stories, nourished by stories. The only way we come to make sense of the world is through the stories we are told. They pattern the world we have fallen into, effectively replacing its terrors and inconsistencies with structured images that assure us of its manageablility."

Yesterday I bought ten Japanese children’s books on my way to work. A woman was having a sidewalk sale on Bedford, and she had a cardboard box full of old board and picture books. When I purchased them, she asked: you can read Japanese? I can read these, I said in English--shy of my atrophied spoken Japanese. One book illustrates the hiragana alphabet, another juxtaposes pictures of animals against their names in Japanese and English. My favorite one is called Hiraku: Open it! One page shows a closed flower or bean pod or shell and says, “hiraku.” The next shows the inside of the object and gives its name.

Nonetheless, upon a second and third flip-through, the pedagogical problem exposes itself: how to avoid the false binary? And the nagging question: what do the smallest things teach? In Hiraku, why don’t these objects get names until their alleged insides are exposed? What about objects that never open? Or of outsides that are always (already) inside? Or if you don't exactly believe in the outside? How can you teach a five year old that the supposed learning technique of inside/outside is a pernicious fallacy that is, as Karen Coates might have it, a kind of management or containment? Couldn't something as early and as simple as a board book instigate necessary disruptions of the kind of knowledge children are idly presented with? After all, what good is radical theory if we wait to inform readers of its importance until they are in graduate school? What sort of initial undoings are also possible?

And then i read Hiraku again, and decided that the imposition of a construct was my own. After all, it's strategy requires opening--not inside and out. Its last few pages also take an interesting turn. The instructions continue:

furoshiki. hiroku to jyuubako.

mata hiroku to gochisou.

Mata hiroku to jyuubako mou hitotsu.

Itadakimasu.

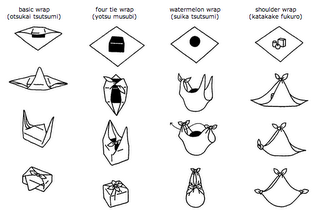

Furoshiki (a cloth used to bundle lunchboxes other packages).

Open it and jyuubako (an elaborate lunchbox/bento).

Open again and treat/feast.

Open again and another jyuubako.

Enjoy.

The reader is given an object wrapped in a furoshiki. Then he or she sees there is a lacquered box inside. Then the box is opened and a feast of sushi and other snacks is revealed. Then another layer beneath the first is exposed. The book's final instruction is for the reader to enjoy the meal.

The furoshiki complicates the open-and-see process. Like language, and like pedagogy, the furoshiki is a process rather than an exposure. A representation of the movement that the exchanges between a and b invite; however, it is also its own sign, a sort of standstill of meaning. It is an object whose purpose might be unproductive: an adornment, a postponement, an end in itself. Additionally, by complicating meaning-making as more than open and shut, hide and seek, the furoshiki calls attention to the complexity of the work of making (ideology) visible. More than a simple "structured image" that assures us of the world's "manageability," it introduces a place of uncertainty.

from Barthes's Empire of Signs:

"These phenomena and many others convince us how absurd it is to try to contest our society without ever conceiving the very limits of the language by which (instrumental relation) we claim to contest it: it is trying to destroy the wolf by lodging comfortably in its gullet. Such exercises of aberrant grammar would at least have the advantage of casting suspicion on the very ideology of our speech."

<< Home