No Love Lost

In Giving an Account of Oneself, Judith Butler injects the possibility of "subversive" self-narration with a dose of productive skepticism:

"When the 'I' seeks to give an account of itself, it can start with itself, but it will find that this self is already implicated in a social temporality that exceeds its own capacities for narration; indeed, when the "I" seeks to give an account of itself, an account that must include the conditions of its own emergence, it must, as a matter of necessity, become a social theorist.The reason for this is that the "I" has no story of its own that is not also the story of a relation—or set of relations—to a set of norms. (8)

Which is not unlike this lassoing of ideology by Jameson:

Postmodernism: "There is...a most interesting convergence between the empirical problems studied by Lynch in terms of city space and the great Althusserian (and Lacanian) redefinition of ideology as "the representation of the subject's Imaginary relationship to his or her Real conditions of existence....The Althusserian formula, in other words, designates a gap, a rift, between existential experience and scientific knowledge. Ideology has then the function of somehow inventing a way of articulating those two distinct dimensions with each other. (Jameson 51-52)

Which nicely echoes the Foucault from yesterday:

"Real subjection is born mechanically from a fictitious relation."

The Butler might be read as one possible step that could follow the provocations from Jameson and Foucault. She is offering a way of tracking this gap between Real and Imaginary, between Real and fictitious. By clouding the obviousness of the "I," Butler complicates the possibility of self-reflexivity and, concomitantly, of agency.

Jameson is also asking, if subjection is dependent upon the illusion, the fictive relation upon which real subjection is built/the imaginary relation to Real conditions of existence, then is it possible to map this relation, and redesign it? Furthermore, if this mapping is not only a proposal, but also a metaphor for practices of reading, then the narrativization OF this process--in other words self-narration or first person narration, and a careful attention to the way in which self-narration is performed, is crucial to what we are ultimately capable of seeing.

To consider a more specific model, if melancholia requires a sort of substitution of the ego for the lost object as a necessary exchange in order for mourning to occur, then what happens if this subject position, that of the ego, is refused? Is this also a refusal of the "I" and, concomitantly, of the conceit of self-narration? Could adolescence function in a similar way? In other words, is it possible that one could, in a process similar to melancholia, refuse adulthood? If this kind of narration is never offered and adolescents are only ever presented with confident self-narrations, will they never think to consider the teleology of adult (pre)occupations? Furthermore, if a narrator cannot distinguish between inside/outside, self/other, might she be inhabiting a truly queered subject position? Are there young adult texts that provide this sort of narration? Might a melancholia in the form of a resistant/prolonged/permanently inhabited adolescence be mobilized as a response to trauma that finds trauma’s foregrounding of the conceit of the self productive? Could a pedagogical attention to the narrative of adolescent fiction suggest to its readership more creative possibilities for subjection? If the "I" could somehow not only be the story of its specific set of relations to a set of norms, but through that narrative also inflect a way of rethinking those norms, might this reflexivity to what we like to pretend is a self be repositioned as subjectivity?

One way to start might be through a pedagogical attention to the differences amongst these beginnings. In other words, when teaching these novels, we could begin by arguing that each narration offers a very different way of thinking about subjectivity, about the possibility of a narrative response to ideology.

The Outsiders (1967): “When I stepped out into the bright sunlight from the darkness of the movie house, I had only two things on my mind: Paul Newman and a ride home.”

The Bell Jar (1971): “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.”

The Catcher in the Rye (1945): “If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

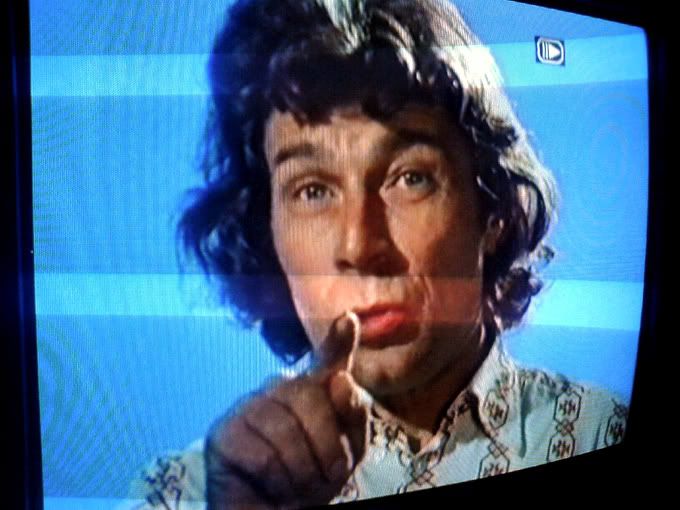

Buddha of Suburbia (1990): “My name is Karim Amir, and I am an Englishman born and bred, almost.”

Rose of No Man’s Land (2006): “People always say to me that they wish they had my family.”

Perks of Being a Wallflower (1999): “Dear Friend, I am writing to you because she said you listen and understand and didn’t try to sleep with that person at that party even though you could have.”

Weetzie Bat (1989): "The reason Weetzie Bat hated high school was because no one understood. They didn't even realize where they were living."

Housekeeping (1980): "My name is Ruth. I grew up with my younger sister, Lucille, under the care of my grandmother, Mrs. Sylvia Foster, and when she died, of her sisters-in-law, Misses Lily and Nona Foster, and when they fled, of her daughter, Mrs. Sylvia Fisher."

<< Home